Python is Fast¶

For Writing, Testing, and Developing of Code

# Hello World in Python

print("hello world")

/* Hello World in Java */

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, World");

}

}

%matplotlib inline

import seaborn as sns

data = sns.load_dataset("iris")

sns.pairplot(data, hue="species");

Python is Slow¶

Compared to compiled languages

# A silly function implemented in Python

def func_python(N):

d = 0.0

for i in range(N):

d += (i % 3 - 1) * i

return d

# Use IPython timeit magic to time the execution

%timeit func_python(10000)

Fortran version:¶

%load_ext fortranmagic

%%fortran

subroutine func_fort(n, d)

integer, intent(in) :: n

double precision, intent(out) :: d

integer :: i

d = 0

do i = 0, n - 1

d = d + (mod(i, 3) - 1) * i

end do

end subroutine func_fort

%%file func_fortran.f

subroutine func_fort(n, d)

integer, intent(in) :: n

double precision, intent(out) :: d

integer :: i

d = 0

do i = 0, n - 1

d = d + (mod(i, 3) - 1) * i

end do

end subroutine func_fort

# use f2py rather than f2py3 for Python 2

!f2py3 -c func_fortran.f -m func_fortran > /dev/null

from func_fortran import func_fort

%timeit func_fort(10000)

Outline¶

Use Numpy ufuncs to your advantage

Use Numpy aggregates to your advantage

Use Numpy broadcasting to your advantage

Use Numpy slicing and masking to your advantage

Use a tool like SWIG, Weave, cython, f2py, Numba, etc. to compile Python or to interface to compiled code.

Fortran is about 100 times faster for this task!

Why is Python so slow?¶

We alluded to this yesterday, but languages tend to have a compromise between convenience and performance.

C, Fortran, etc.: static typing and compiled code leads to fast execution

- But: lots of development overhead in declaring variables, no interactive prompt, etc.

Python, R, Matlab, IDL, etc.: dynamic typing and interpreted excecution leads to fast development

- But: lots of execution overhead in dynamic type-checking, etc.

We like Python because our development time is generally more valuable than execution time. But sometimes speed can be an issue.

Strategies for making Python fast¶

Use Numpy ufuncs to your advantage

Use Numpy aggregates to your advantage

Use Numpy broadcasting to your advantage

Use Numpy slicing and masking to your advantage

Use a tool like SWIG, cython or f2py to interface to compiled code.

Here we'll cover the first four, and leave the fifth strategy for a later session.

Strategy 1: Use ufuncs to your advantage¶

A ufunc in numpy is a Universal Function. This is a function which operates element-wise on an array. We've already seen examples of these in the various arithmetic operations:

a = [1, 3, 2, 4, 3, 1, 4, 2]

b = [val + 5 for val in a]

print(b)

import numpy as np

a = np.array(a)

b = a + 5 # element-wise

print(b)

The speed of ufuncs¶

a = list(range(100000))

%timeit [val + 5 for val in a]

a = np.array(a)

%timeit a + 5

Other ufuncs¶

There are many, many ufuncs available:

- Arithmetic:

+ - * / // % ** - Bitwise Operations:

& | ~ ^ >> << - Comparisons:

< > <= >= == != - Trig Functions:

np.sin np.cos np.tan...etc. - Exponential Family:

np.exp np.log np.log10...etc. - Special Functions:

scipy.special.*

and many, many more.

Strategy 2. use aggregations to your advantage¶

Aggregations are functions over arrays which return smaller arrays.

Suppose you want to compute the minimum of an array

from random import random

c = [random() for i in range(100000)]

%timeit min(c)

c = np.array(c)

%timeit c.min()

Aggregates along axes¶

M = np.random.randint(0, 10, (3, 5))

M

M.sum()

M.sum(axis=0)

M.sum(axis=1)

Other Aggregation Functions¶

Numpy has many useful aggregation functions:

np.min np.max np.sum np.prod np.mean np.std np.var np.any np.all np.median np.percentile np.argmin np.argmax

Most also have a NaN-aware equivalent:

np.nanmin np.nanmax np.nansum ...etc.

Strategy 3: Use Broadcasting to your advantage¶

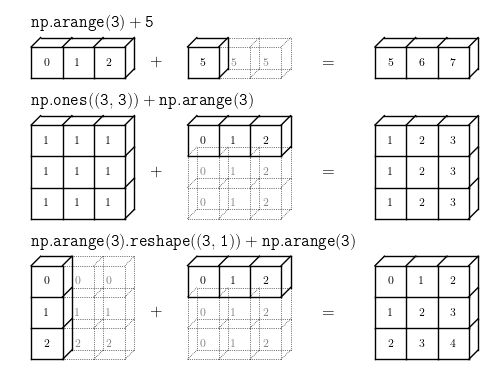

Broadcasting in NumPy is the set of rules for applying ufuncs on arrays of different sizes and/or dimensions.

np.arange(3) + 5

np.ones((3, 3)) + np.arange(3)

np.arange(3).reshape((3, 1)) + np.arange(3)

Visualizing Broadcasting¶

Rules of Broadcasting¶

If array dimensions differ, left-pad the smaller shape with 1s

If any dimension does not match, stretch the dimension with size=1

If neither non-matching dimension is 1, raise an error.

Examples¶

Example 1¶

M = np.ones((2, 3))

M

a = np.arange(3)

a

M + a

Example 2¶

a = np.arange(3).reshape((3, 1))

a

b = np.arange(3)

b

a + b

Example 3¶

M = np.ones((3, 2))

M

a = np.arange(3)

a

M + a

Strategy 4: Use slicing and masking to your advantage¶

The last strategy we will cover is slicing and masking.

Python lists can be indexed with integers or slices:

L = [2, 3, 5, 7, 11]

L[0] # integer index

L[1:3] # slice for multiple elements

NumPy arrays are like lists¶

L = np.array(L)

L

L[0]

L[1:3]

Masking¶

L

mask = np.array([False, True, True,

False, True])

L[mask]

mask = (L < 4) | (L > 8) # "|" = "bitwise OR"

L[mask]

Fancy Indexing¶

L

ind = [0, 4, 2]

L[ind]

Multiple Dimensions¶

M = np.arange(6).reshape(2, 3)

M

# multiple indices separated by comma

M[0, 1]

# mixing slices and indices

M[:, 1]

# masking the full array

M[abs(M - 3) < 2]

# mixing fancy indexing and slicing

M[[1, 0], :2]

# mixing masking and slicing

M[M.sum(axis=1) > 4, 1:]

Putting it All Together¶

Nearest Neighbors of some data

# 1000 points in 3 dimensions

X = np.random.random((1000, 3))

X.shape

# Broadcasting to find pairwise differences

diff = X.reshape(1000, 1, 3) - X

diff.shape

# Aggregate to find pairwise distances

D = (diff ** 2).sum(2)

D.shape

# set diagonal to infinity to skip self-neighbors

i = np.arange(1000)

D[i, i] = np.inf

# print the indices of the nearest neighbor

i = np.argmin(D, 1)

print(i[:10])

# double-check with scikit-learn

from sklearn.neighbors import NearestNeighbors

d, i = NearestNeighbors().fit(X).kneighbors(X, 2)

print(i[:10, 1])

Summary: Speeding up NumPy¶

It's all about moving loops into compiled code:

Use Numpy ufuncs to your advantage (eliminate loops!)

Use Numpy aggregates to your advantage (eliminate loops!)

Use Numpy broadcasting to your advantage (eliminate loops!)

Use Numpy slicing and masking to your advantage (eliminate loops!)

Use a tool like SWIG, cython or f2py to interface to compiled code.